The Queer Fashioning of British Vogue: The Lesbian Couple who Modernized Fashion Journalism (1922-1926)

In just four short years Dorothy Todd and Madge Garland brought the novelty of modernity to the pages of British Vogue, transforming the publication into a forum for the modernist avant garde.

For my first Substack article I really wanted to touch on a topic that covers two of my special interests: 1920s fashion and lesbians. As a connoisseur of fashion history, some of the things that I consider to be the essentials include the following: the S bend corsets of the Edwardian era, flapper fashions of 1920s youth, Dior’s (1947) Bar Suit, 1970s politically fashioned bell bottoms, 1990s supermodels (The Big Five) and Vogue.

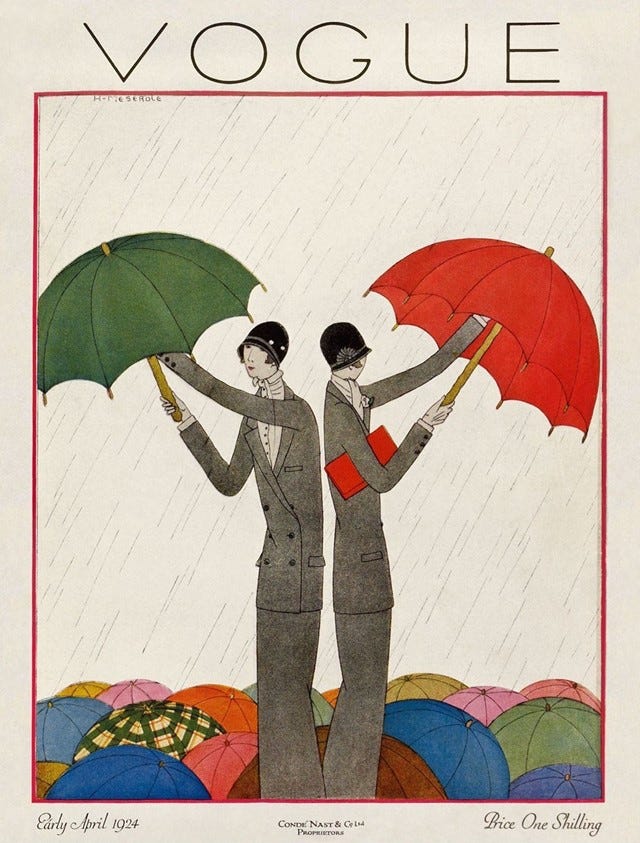

I think most people would agree on the last item of this list. Lesbian Fashion Historian Eleanor Medhurst said about the publication in her book Unsuitable, A History of Lesbian Fashion: “Vogue etched its title onto the twentieth century fashion landscape as a tasteleader: a fount of the modern and the stylish.” Vogue in its early years was considered to be a platform for modern tastemakers, and this movement of modernity in fashion was led in part by two lesbians. According to Christopher Reed, “by casting off sexual mores like out-of-date corsets, Vogue’s extensive coverage of literature and the arts became a guide to an emerging canon of queer modernism.”

The name of the publication has taken on different forms, staying in the consciousness of both those who would and wouldn’t consider themselves invested fashion journalism consumers, alike. One of my fashion history professors at FIT defined fashion for me on our first day of class as “the style of dress adopted in a society for the time being,” meaning that fashion is dynamic and never stationary. For something to be considered “fashionable” it has to come and go “in and out of fashion” (or, “in and out of Vogue”).

Dorothy Todd and Madge Garland worked hand in hand at British Vogue as Editor and Fashion Editor for about half of a decade, pioneering the energetic spirit of jazz age fashion journalism. As described by their contemporary Rebecca West, they “changed Vogue from just another fashion paper to being the best of fashion papers and a guide to the modern movement in the arts (Medhurst).” Just as the nature of fashion trends, their time at the magazine came and went and was eventually forgotten.

The 1920s and the Birth of Modern Dress

War, of course, had major implications on the fashions of the early 20th century. Textiles were needed for military use during WW1 and individuals were urged to do their part in conserving fabric. Realities of wartime resulted in a somber color palette of neutral tones, and black (the color of mourning dress). As a result, there was an overall simplification in fashion and the rituals of getting dressed, especially in comparison to Victorian dress practices.

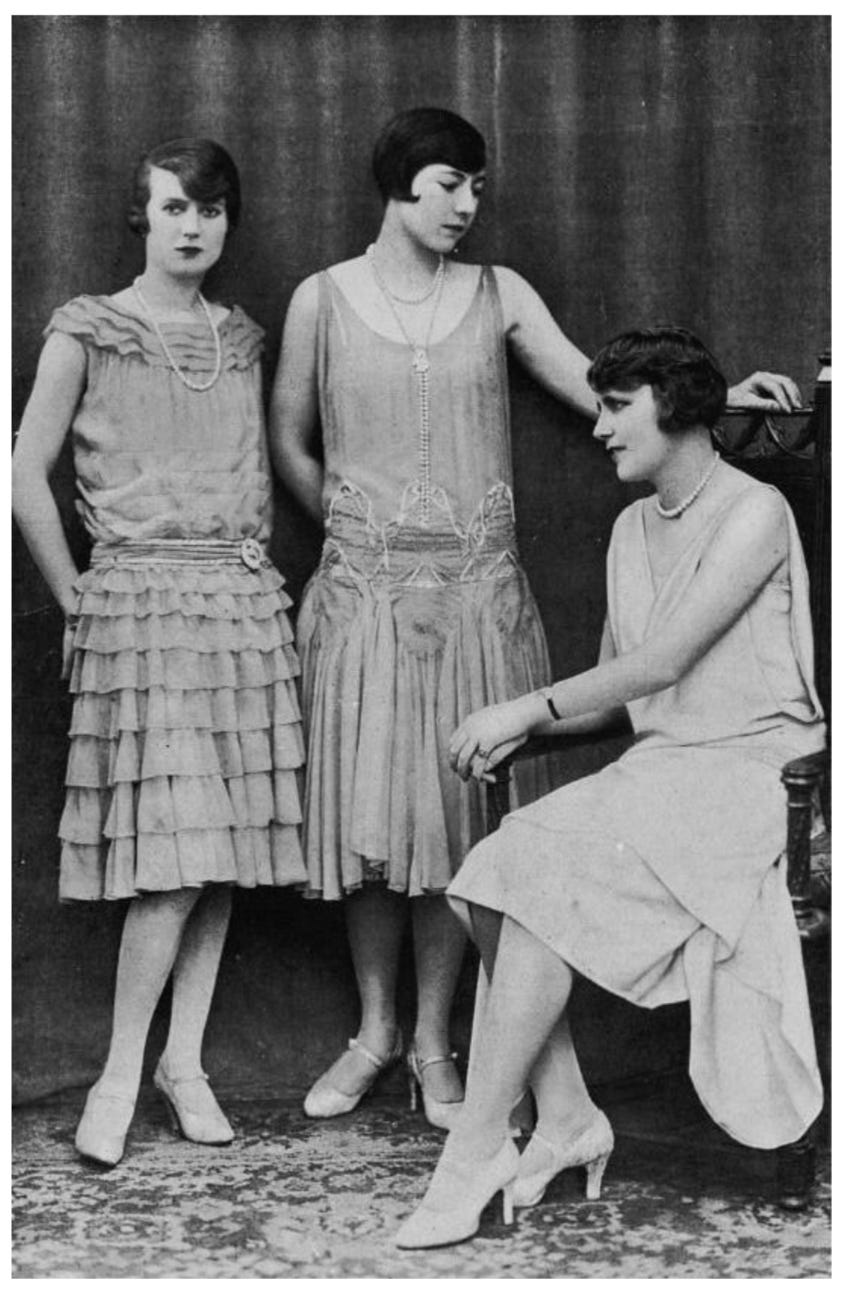

After this period of economic uncertainty post-WW1, a euphoric sense of relief filled the streets of major cities. A pleasure filled, buoyant spirit could be felt in the air of the 1920s. Cars became popular and widespread and new exciting dance trends like the Charlestron led to clothing styles suited for movement. As men returned from battle and society began to attempt a resuming of normalcy, a sense of modernity became apparent. This modernity presented itself quite fashionably in the form of tubular, boyish, shimmering beaded dresses paired with illustrious strings of pearls worn by daring young women and girls (mostly after dark). Similar, more demure versions of these styles reigned in popularity while the sun was still up (The History of Modern Fashion, Cole, 2015).

The beauty industry took off around this time, as more women began to wear more daring shades of rouge and eye shadow. Prior to this, makeup was associated with sex work and was frowned upon when applied heavily. Now iconic brands, like Max Factor and Maybelline who emerged in the decade prior, grew in popularity.

The major political events of the 1920s significantly contributed to the celebratory spirit of the decade and influenced the modernization of women's dress. The 18th Amendment, which established Prohibition, led people to seek out ways to drink, resulting in the creation of speakeasies—third spaces where women and men could socialize more freely. The 19th Amendment, granting (mostly white) women the right to vote, marked a forward movement for women in society. Both amendments facilitated a shift away from traditional ideas of women's dress towards higher hemlines and conspicuous consumption, reflecting a broader cultural movement towards greater freedom and expression.

In the arts, Surrealism, Cubism and Orphism used color and uncanny imagery to celebrate the shifting qualities of modern life. Queer writers and photographers like Virginia Woolf and Cecil Beaton expressed both the pleasures and anxieties of the period through their work in various mediums (The History of Modern Fashion, Cole, 2015).

Another sartorial shift of the 1920’s was the popularization of the “La Garconne” look which directly translates to “The Tomboy.” This look, characterized by garments that called for a more boyish silhouette, was a major departure from the S bend corsets of the decade prior. The name of this look was inspired by a 1923 novel by Victor Margueritte about a woman who, upon discovering her husband's adulterous habits, opts for a freer life, exploring her sexual identity through romantic and sexual relationships with both men and women. Androgyny in fashion drew a finer line between women’s and men’s styles, as it became en Vogue for girls and women who lived fast, urban lifestyles to sport cropped hair (specifically, an Eton Crop) paired with men's fashions. Pop culture figures of the time like Louise Brooks sported the La Garconne look, complete with a modernist attitude that can be summed up in a quote by Brooks; "I like to drink and fuck” (Embla).

All of these cultural shifts in the late 1910’s and into the early 1920’s prepared people of the UK for the editorship of Vogue under Todd and Garland.

Modernist Madonnas

One could say our pair found love in a hopeless place: the dingy office of what was British Vogue in the early 1920’s. “Brogue” was founded in 1916, when complications of WW1 resulted in the rationing of paper production in the US and Conde Nast had difficulty shipping print overseas (Medhurst). The journalistic story of our lady lovers begins in 1923 when Edna Woolman Chase, Condé Nast’s director of the American, British, German, and French editions of Vogue appointed Dorothy Todd the position of Editor at British Vogue, headquartered in London. Todd became the second editor ever at the UK leaf of the publication following her predecessor Elspeth Champcommunal. This event was exceptionally revolutionary being that Todd was openly gay, and in lesbian relationships.

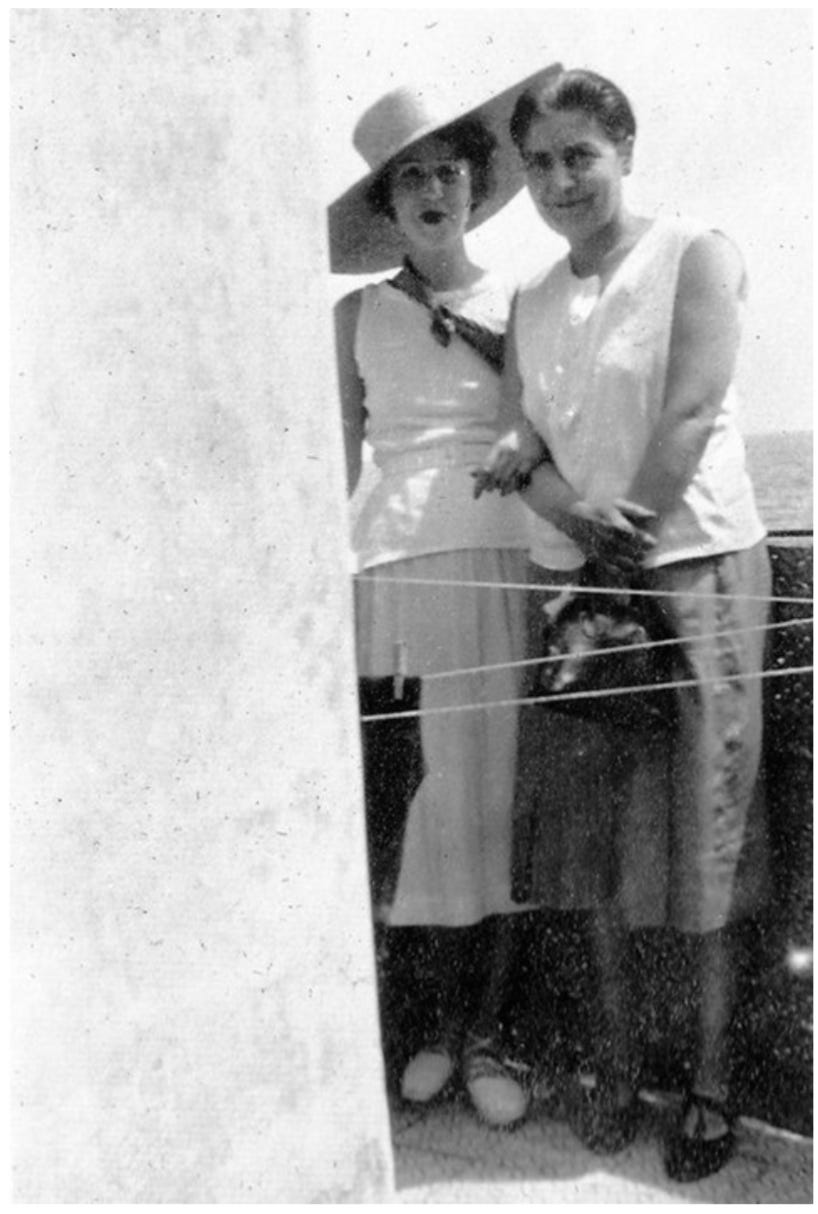

While at the magazine, Todd met 26-year-old Garland. Immediately charmed by her beauty and wit, she gave her the title of fashion editor (Medhurst). Garland’s first position at the office beginning in 1919 is what we now think of when hearing the words "fashion intern”: going on coffee runs and working poorly paid, long hours. Think Andrea Sach from The Devil Wears Prada, pre-movie makeover. One could argue this was a major upgrade.

Garland was born in Melbourne, Australia on June 12th 1896, moving to London with her family at just age two. Similar to Todd she has been described as a creative, curious, bookish child (Zachary, Calahan). Garland grew into a lanky and expressive woman, never not decked out in the latest fashions during her reign as Brogue fashion editor. Garland was described by fashion photographer Cecil Beaton as the embodiment of 1920s high fashion, dressed by all of the greatest forward thinking, avant garde couturiers of the day including the likes of Gabrielle Chanel, Jeanne Lanvin, Jean Patou and my favorite, Elsa Schiaparelli.

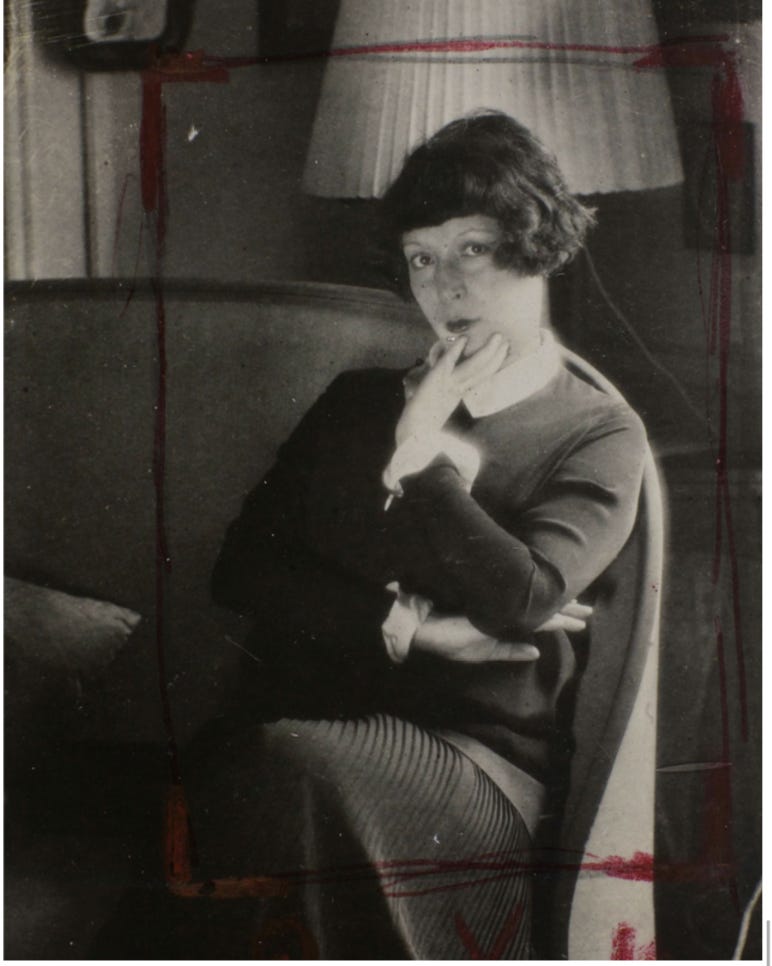

Born on May 1st 1883, Dorothy Todd at best has been described as “mannish” and at worst “Butch as Pig Iron.” During her life she was compared to a range of animals actually, including a sea lion and a badger. Todd presented as a masculine lesbian, often sporting menswear garments paired with a pleated skirt, in order to feminize her look and make it socially palatable. This was a common way of dressing for lesbians of the 20’s, paired with a monocle or a violet pinned to a lapel (a reference to Sappho). There are written records of Todd wearing full menswear ensembles, however, the few surviving photos of her do not reflect this description.

Written physical descriptions of Garland note her thinness, femininity and style. Note the stark contrast between the stories told of Todd and of Garland: the mannish, pig-like-butch and her waifish, blonde, feminine counterpart. I would feel as though I had done a disservice to their individual stories if I did not address this historial pattern regarding the poor treatment of GNC lesbians and queer women, particularly butches.

The nature of Todd’s aggressively queer appearance I believe is symbolic of her goal at the magazine: to push the limits of what people were comfortable with. Unlike her predecessor Champcommunal, whose focus was on travel and fashion trends, Todd dedicated the pages of British Vogue to highlighting queer artists who were leading figures in modernism. This desire to reshape the magazine would eventually be the demise of her time period of editorship. Condè Nast did not particularly love the notion that she “lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles'' (Jones).

Fashions for Inverts

During the years of 1922-1926, under Todd and Garland, the publications offerings reached far outside the realm of fashion, including emerging modern artists, often queer theater productions, and interior design, regularly showcasing new fashion photographers. The women made sure the publication recognized the changing nature of the landscape of not only fashion but all other artistic fields, making British Vogue one of the earliest publications to make a convincing argument that fashion should be taken as seriously as other forms of art and material culture.

One editorial from early April 1925 announces, “Vogue has no intention of confining its pages merely to hats and frocks” concluding “in literature, drama, art, and architecture the same spirit of change is seen at work” (Reed). Many of these artistic luminaries rejecting tradition and embracing modernity happened to be queer (shocker). British Vogue during the years of Todd’s editorship became a haven for queer creatives who were supported and uplifted by the couple through both their financial patronage and friendship. Eleanor Medhurst has written how when placed in the context of British Vogue, “modernism became a code for queerness.”

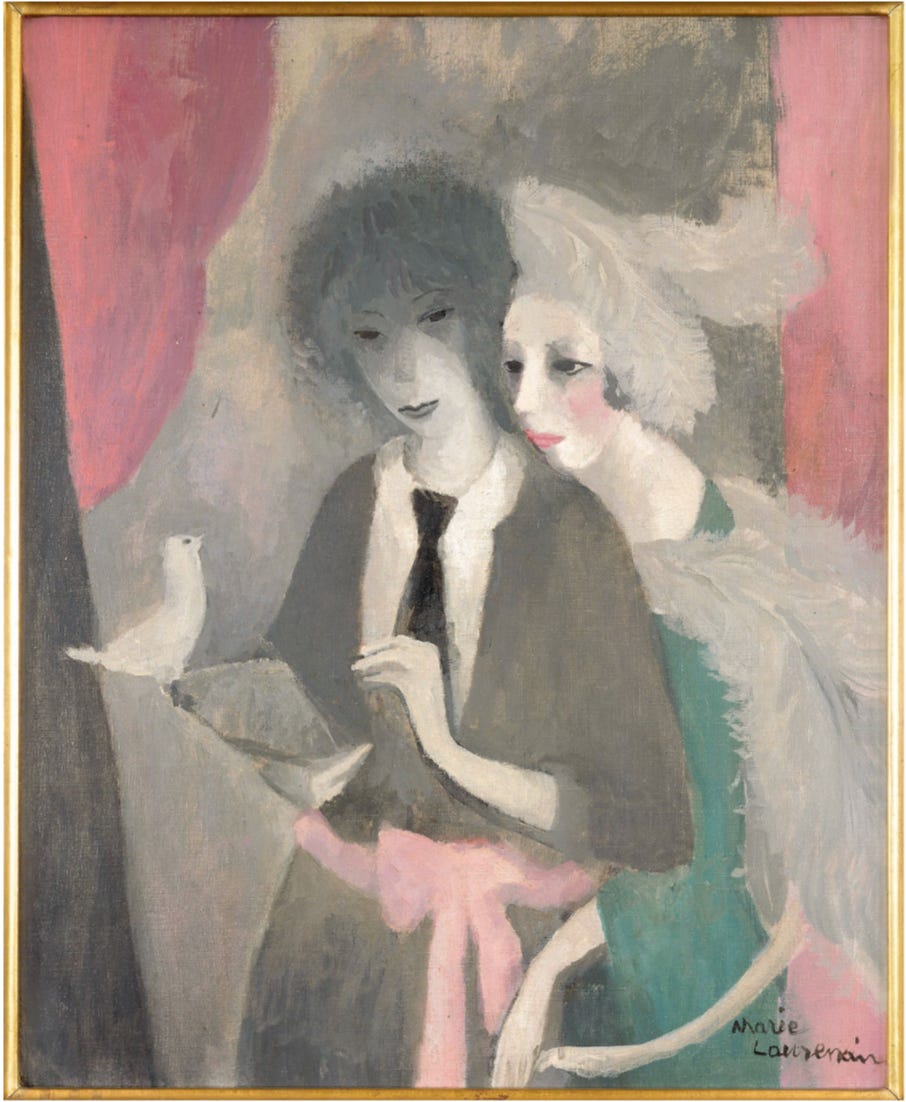

In January 1925, British Vogue published a work by the French painter Marie Laurencin referring to her as “the sister of Sappho” (Reed). Although she was never forthcoming with her sexual identity, Laurencin spent many nights in Parisian lesbian bars, and congregating with other known lesbian artists such as Gertrude Stein.

A caption of another of Laurencin’s works published under Todd in early December 1924, which depicts frolicking women and animals, notes how within the “new poetic world” of the painter's mind, there are “slim girls…, horses, dogs, and birds, but never a man (Reed).”

It has also been speculated that Laurencin most often refused to paint men, charging higher than her usual commission fee for the few times she relented (Zachary, Calahan). Her work is glittering with soft hues of pink and blue, animals and intimate gestures shared between both hyper feminine and masculine women. In the words of Enya Umanzor, “Why would a man be there?”

My personal favorite work by Laurencin is a self portrait of her alongside early 20th Century couturier Nicole Groult, the sister of another great modernist designer, Paul Poiret. Groult “wrote poetry to her describing her eyes, breasts and lips as birds” (Palumbo). The dove gazing upon the women is said to represent sapphic love, as if the intimate, amorous nature of the two was not obvious enough. Laurencin’s vision of a utopian world full of only women, graced the pages of British Vogue alongside spreads of illustrated cartoons, similarly homosexual in nature.

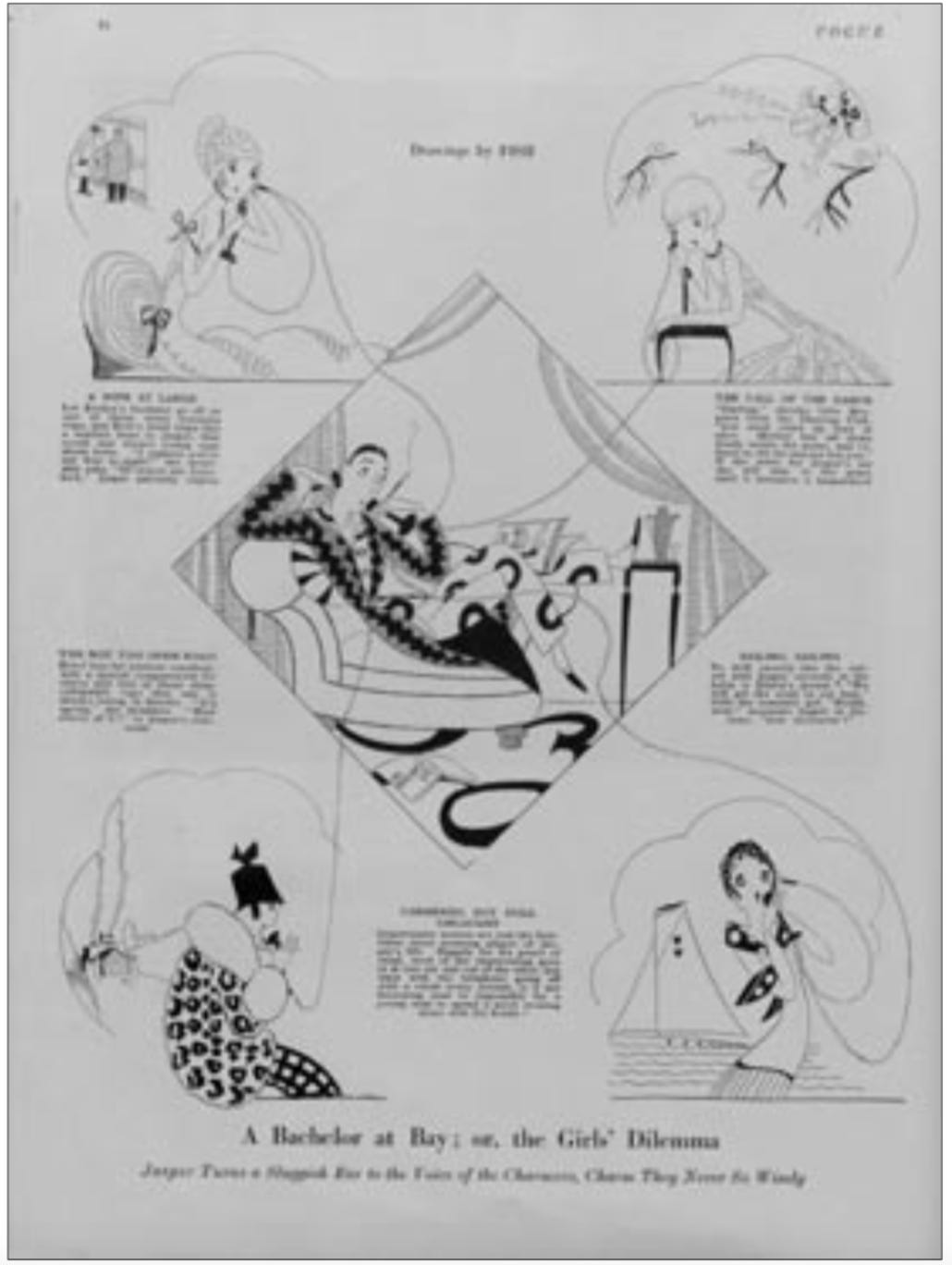

The fluidity of gender and eroticism is especially clear in these Vogue cartoons on modern mores of the 1920s. Illustrations often told stories of a satire courtship and marriage with an array of men avoiding (or failing) at heterosexual coupling. “A Bachelor by The Bay” by a cartoonist going by the pseudonym “Fish” exhibits an eligible bachelor named Jasper, who declines female advancements in order to stay home in his silk robe, reading the saucy french novel La Garconne (Reed). That title ring a bell?

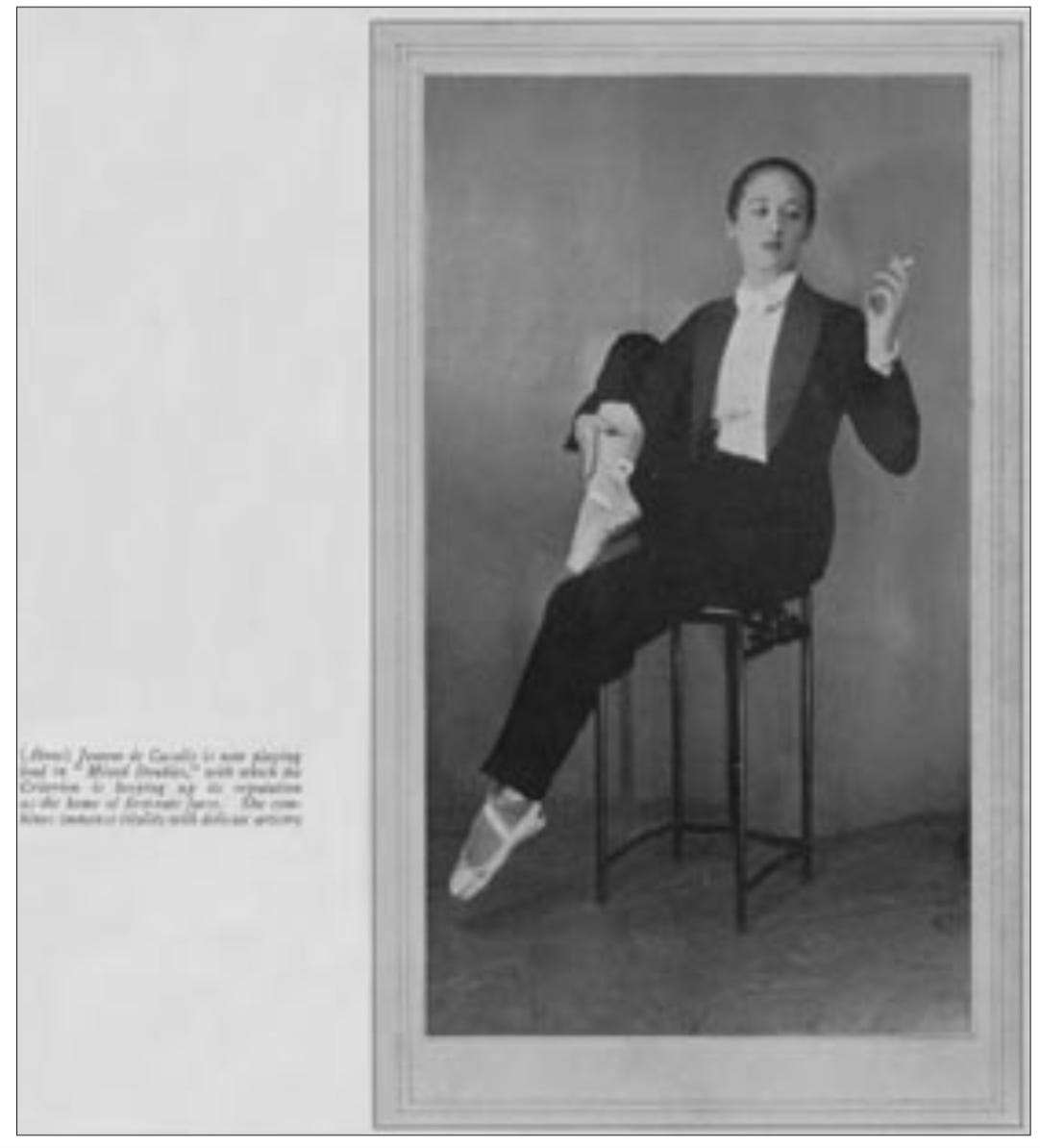

Frequent allusions to a sexual subculture not only kept readers aware of developments within these communities but also encouraged a wider audience of fashionable women to align themselves with the modern openness to new, queer ideas. Images of beautiful, androgynous women of the silver screen donning suits and cropped hair graced the pages of Todd and Garland’s Vogue intended to convince women of the latest mode. A selection of these photographs which fell under “seen on stage” relay the magazine's fascination with women in masculine dress, among them the handsome Varda in her “dangerously attractive” tuxedo (Reed). The ballet flats with the tux? Come on, so good.

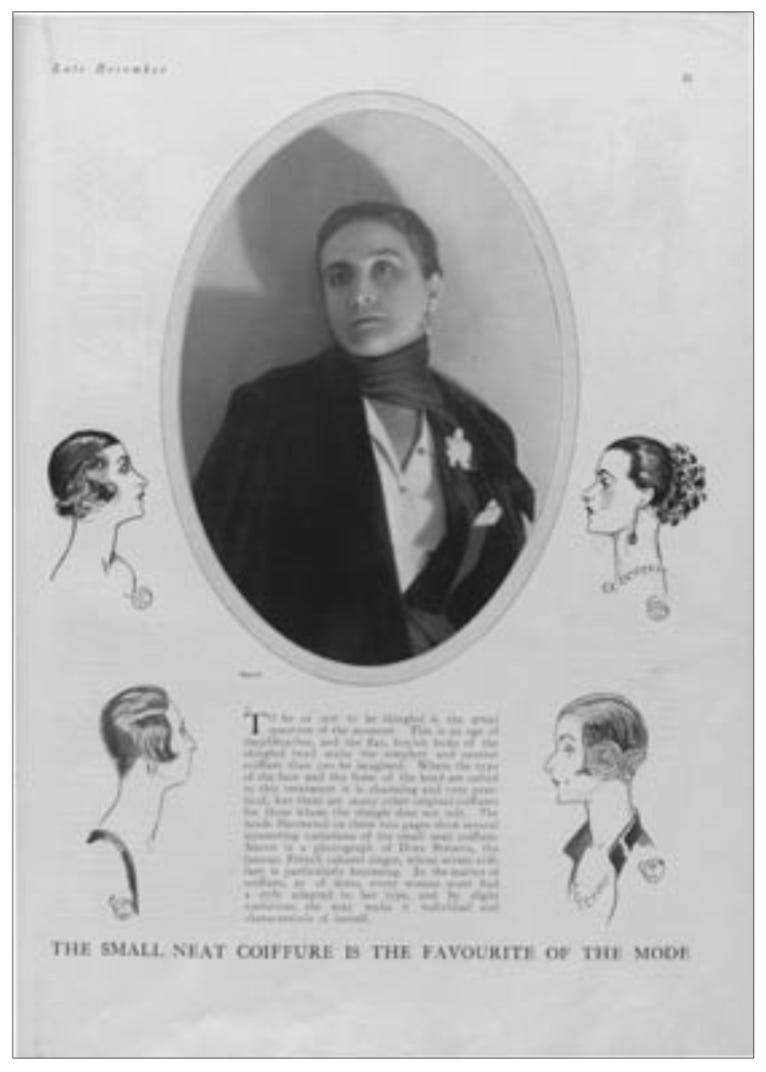

A feature on hairstyles in late December 1923 left readers to their own conclusions (or fantasies) about the beautiful butch woman with short hair and a masculine fashion sensibility known as Dora Stroeva. The feature hinted at a broader sexual subculture, suggesting that readers might need some preexisting knowledge to fully appreciate the advice on achieving "the flat, boyish locks of the shingled head (Reed)." The illustrations surrounding a portrait of Stroeva include four variations of a boyish cut considered to be the new mode, according to our two lovers. The choice of using Stroeva and Varda as faces of ideal 1920s beauty sent a signal about the incoming change in regards to fashion for women and gender fluidity: the modern world was one that celebrated queerness. This depiction of gender-fluid eroticism by Todd and Garland in Vogue is a notable contribution to the modernism of the 1920s, challenging traditional gender norms and influencing contemporary styles.

Other queer contributors included gay literary critic Raymond Mortimer, Virginia Woolf and one of her lovers Vita Sackville-West who regularly wrote columns for the magazine. Cecil Beaton, who is arguably one of the most iconic and influential fashion photographers of the 20th century, had one of his first photographs published under the editorship of Todd and Garland. In particular, Beaton is known for his photographs of groups of young queer people which he lovingly referred to as “the bright young things.”

During the interwar period, Beaton became known for “swooning and romantic portraits of Britain’s thinking classes, where broad strokes of fantasy and artifice stood as a defiant rebuke to the austerity of post-war life” (Moss). These young people along with other contributors I’ve spoken of were able to explore gender and sexual identity by hiding behind “fashion” or fancy dress parties. Exorbitant wealth provided third spaces for queer individuals to hold parties with dress codes, or rather no dress code. Whimsical images of boys and men in drag and women in masculine attire defined a subset of fashion photography of the 1920s. The whimsical and the contemporary quality of these images affirm a certain instinct in the hearts of many queer people: that we've always been the same. Issues of Vogue accessible through digital catalogs hold visual proof of queer stories and their integral role in producing culture.

Sarah Cheang says in her article, “To The Ends of the Earth: Fashion and Ethnicity in the Vogue Fashion Shoot” that “the concept of fashion that the Vogue title encapsulates is predicated on a series of interrelated ideas about modernity, cosmopolitanism and individual identity construction in an aspirational consumer culture.” The culture of modernism during the 1920s was built up by queer artists, writers and their contemporaries. These ideas of modernity and the construction of both personal identity and consumer culture began on the pages of Vogue under the editorship of two lesbians. For this reason, I believe that queer history is fashion history is queer history. This Substack will be dedicated to my favorite stories that make up mostly 20th century fashion, because this is my favorite area of study. Many of these stories will be queer ones, which I hope excites all of you little gay (and not) people in my phone.

References

Beaton, Cecil (2004). Beaton in the Sixties: The Cecil Beaton Diaries as He Wrote Them, 1965-1969. Vol. 2. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 30 note 3. ISBN 9781400042975.

Dressed: The History of Fashion. (n.d.). Fashion lovers: Dorothy Todd and Madge Garland. Apple Podcast.

Jones, Eleanor. (2024, April 11). Painting in circles and loving in triangles: The Bloomsbury Group’s queer ways of seeing. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/painting-in-circles-and-loving-in-triangles-the-bloomsbury-groups-queer-ways-of-seeing-75438

Jones, G. (2021, September 12). Madge Garland, the fashionista who changed Britain. Blue17 vintage clothing. https://www.blue17.co.uk/vintage-blog/madge-garland/

Medhurst, Eleanor. (2020, December 3). Fashion history was never straight: Madge Garland, Dorothy Todd and Vogue. Dressing Dykes. https://dressingdykes.com/2020/11/27/fashion-history-was-never-straight-madge-garland-dorothy-todd-and-vogue/

Medhurst, Eleanor. (2024). Unsuitable: A history of lesbian fashion. Hurst and Company.

Pentelow, Orla (28 December 2017). "Vogue Editors Through The Years". British Vogue. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

Reed, Christopher (2006). "A Vogue That Dare Not Speak Its Name: Sexual Subculture During the Editorship of Dorothy Todd, 1922–26". Fashion Theory. 10 (1–2). Informa UK Limited: 39–72. doi:10.2752/136270406778050996. ISSN 1362-704X. S2CID 193363060.

“To the ends of the Earth”: Fashion and ethnicity in the vogue fashion shoot. Bloomsbury Visual Arts-’To The Ends of The Earth’: Fashion and Ethnicity in The Vogue Fashion. (n.d.). https://www.bloomsburyvisualarts.com/encyclopedia-chapter?docid=b-9781350051201&tocid=b-9781350051201-chapter3

User, G. (2020, September 1). La Garconne 1920’s. PURVEYOR. https://www.purveyour.com/discover/la-garconne-1920s

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, October 26). Dorothy Todd. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Todd

Incredible article! I’m wondering which Valerie Steele article you’re referencing for the images? When you click on the link it takes you to the FIT library website where you need institutional access. I’m interested in using one of the images you used here for my Master’s dissertation and need some more information on the image!

Thanks!

Beautifully written!