A History of Egyptomania in Material Culture: Two Hundred Years of Sartorial Orientalism (Installment #1)

Scarab beetles and falcons galore! Once you see it, you won’t be able to unsee it.

My interest in Egyptian influence on Western fashion begins, as many of my sartorial obsessions do, in a vintage store. One day at my former job, my boss showed me this wonderful black netted textile, with bits of metal woven into it in the shape of geometric Art Deco designs. She told me that this shawl was called “Assuit” (or “Asyut”) informing me of its Egyptian origins. I went home, did some research (looked on eBay for one to purchase), and was displeased to find that these collector’s items could only be purchased at a high price point. Another day in the shop, I found myself admiring a green beetle-shaped brooch, and with a quick google search I learned that I was looking at an Egyptian revival Scarab.

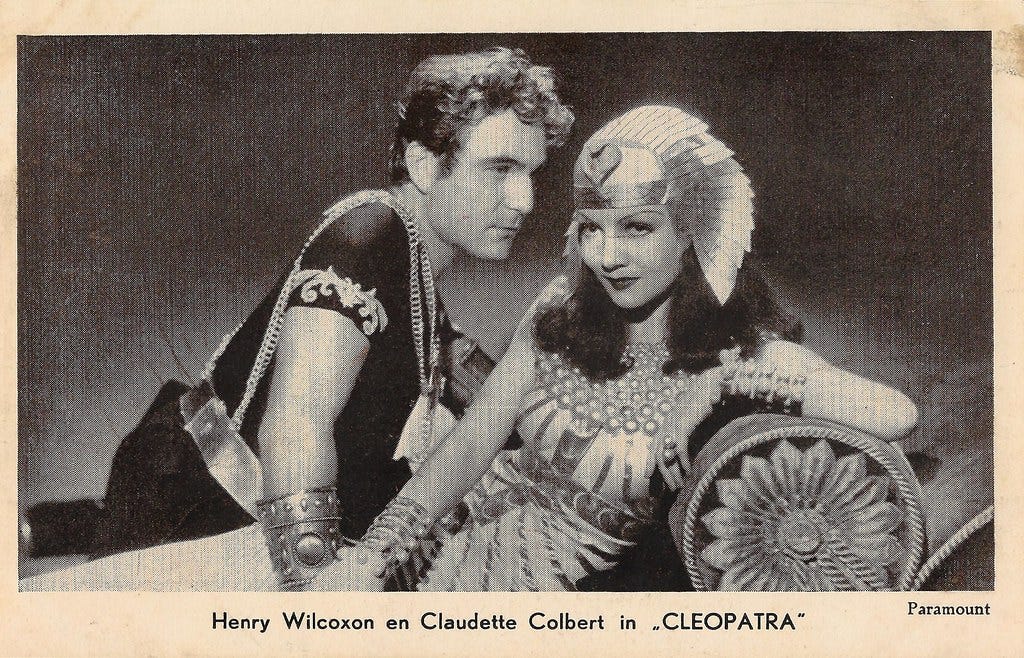

This semester, I took a class on Costume and Fashion in Film, and was assigned a costume analysis paper for my final. I decided to use this assignment as an excuse to watch two films that had been sitting in my notes app “watch list” for some time, as well as do an Egyptian revival deep dive. I began my on-screen Egyptomania journey with Cleopatra (1934) starring the bewitching Claudette Colbert. I also watched Cleopatra (1963) starring Liz Taylor, which I quite honestly found to be extremely dull to watch. However, certain elements of the costumes are historically-informed, and worth noting. After watching both films, I decided I wouldn’t be able to analyze costumes without a deeper understanding of the origins of Egyptian-inspired Western fashions. I have decided to post my research in a three-part series. The first will be a broad (general) history of Egyptomania in Western visual arts, with a focus on fashion and costume design. The second will be a costume analysis of the designs by Travis Banton and Irene (Renie) Conley in Cleopatra (1934), and Cleopatra (1963) respectively. Finally, the third part will be on twenty-first century Egyptomaniacs, the sartorial influence of these films, as well as a broader image of the enduring cultural effects of Western Egyptomania. So, I begin with defining Egyptology, Egyptomania, and the origins of this Western phenomenon.

Egyptomania can be broadly defined as a Western fascination with ancient Egyptian culture. Historical periods where material culture produced by the Western world frequently depicts imagery and motifs associated with ancient Egypt, are referred to as periods of Egyptian revivals. Historically speaking, each more contemporary revival has been preceded by a discovery of sorts, making available new information about ancient Egyptian culture to the global West. Both socio-political events and archeological discoveries can be attributed to this Western cultural sensation. The French’s invasion of Egypt in the 1790s, the discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1923, and the subsequent traveling exhibition of the items in the tomb, (which made its way around American museums between the years of 1972 to 1981) contributed greatly to various, intense waves of Egyptomania. Each event, post-late eighteenth century, sparked a new wave of widespread “Egyptianized” fashions for women.1

Egyptian revival creations in the realm of furniture, architecture, paintings, clothing, costume, and accessories, can be characterized by the use of motifs related to, or of fictional depictions, of the Orient, ignoring both the reality of ancient and modern Egypt simultaneously. Egyptomania is just one of many examples of Anglophone and European orientalism which draws a mystical, fantastical, exoticized vision of a non-Western terrain. These ideas and visuals are impressed onto American material culture, allowing the West to enjoy and imagine an oriental landscape.

Napoleon Bonaparte is often considered one of the first recorded historical examples of an Egyptologist, meaning someone who studies the history, culture, and language of Egypt. This description is arguably much too complimentary: Napoleon led an imperialist mission in 1798, leading the French army to invade Egypt, quickly conquering both Alexandria and Cairo. After arriving home in France, Napoleon wrote his multi-edition Description de l’Égypt (Description of Egypt). 2

Published in 1908, this seminal text became the Egyptomania bible for artists in the early nineteenth century, who obtained their images of Egypt from Napoleon's fictionalized, romantic depictions of “the Orient.” Over the span of the nineteenth century, fictionalized Egyptian motifs, most likely inspired by this piece of French literature, became particularly popular among both architects and furniture designers. Figure 1 displays the gates of the Mount Auburn Cemetery located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, built in 1832, which includes the first example of Egyptian motifs implemented in a structure in the United States.3

Later examples of Egyptomania in visual arts can be seen in furniture design. An armchair by the Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Company located at the Metropolitan Museum of New York City depicts a Pharaoh's head, along with other more vaguely Egyptian motifs.

With fictionalized Egypt carved into buildings and woven into pieces of furniture, “people of the Western world could impress their white bodies onto foreign landscapes” says scholar Lea Stephenson. These willful, white reinterpretations of ancient Egypt seemingly bridged the gap between modern Westerners and oriental antiquity. Primarily towards the end of the century, this fictional version of Egypt found its way onto costume and dressmakers’ sartorial creations as well.4

Post-Napoleonic Mission Egyptomaniacs

Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, in conjunction with the publishing of his multi-edition Description de l'Egypt (Description of Egypt) in 1808, resulted in a range of Egyptian-inspired fashionable trends in women’s dress beginning in the first decade of the nineteenth century. Empress Eugénie de Montijo’s stories of her enjoyed time on the Nile, along with the unpacking of her suitcase filled to the brim with Egyptian goods, resulted in one of the first waves of Egyptomania specifically in women’s fashion. According to oral accounts, Eugenie’s travel mementos sent the Tuilerie into a frenzy with “all the rich presents brought back from Egypt consisting of shawls and [other treasures] from the Levant, jewels, and objects of curiosity bearing the mark of their Eastern origin.” The French, and more broadly the West, were enraptured by her Oriental treasures of curiosity.5

Around the turn of the century, Eastern tunics (shawls) brought back on this infamous trip, referred to as “Mamluks” or “Mamelucks” by fashion magazines, began to be worn over neoclassical, column gowns of fashionable ladies. The name Mameluck seemingly derives from the mamluk period of Egypt (1250-1517). This Arabic word directly translates to “slave”, or “owned” in English. The Mamluk capital of Cairo, “became the economic, cultural, artistic center of the Arab, Islamic world.”6

These sumptuous layered silk textiles were common in Europe from the years 1802 to 1810, until more complicated dress styles grew popular among women, which no longer called for drapery around the shoulders to accessorize. Egyptian-inspired “turbans” enjoyed a period of popularity around the same time as well (as depicted in figure 7). Colors associated with Egyptian dress in the 1820s grew in popularity among dressmakers, such as a shade of warm ochre referred to colloquially in France as Terre d'Egypte (Land of Egypt) as well as a shade of teal-green called Scarabée (scarab/beetle). Despite this range of early “Egyptianized fashions,” Egyptomania did not take off as an internationally widespread Western sartorial phenomenon until the latter half of the century. However, once Americans picked up on this trend, it became an ill-fated touchstone of Anglophone and European fashion history, influencing designers for decades to come.7

Gilded Age Orientalism at Fancy-Dress Costume Parties

Gilded Age New York (1870 to approx.1900) was a period riddled with extreme economic inequalities. A small number of families who accumulated wealth from the technological advancements of the final decades of the century became known as the nouveau riche (new money). Similar to their old-money counterparts, they greatly enjoyed regularly throwing fashionable fancy dress and costume parties to conspicuously display their ostentatious wealth. These gatherings were a popular practice among ultra-wealthy social circles and were an essential aspect of New York Gilded Age social life. Great importance was placed on preparing decadent costumes and ensembles for these events, which would most often be photographed. Taking inspiration from “Egyptian” inspired designs emboldened by Napoleon's expedition in 1798, orientalist fashions and costumes became the rage, frequently donned by wealthy women to these social gatherings.

Figure 8 pictures New York socialite, Lady Arthur (Mary) Paget dressed for the 1875 Delmonico Ball, her corseted figure trimmed with small gold Pharaoh heads, and embellished with Egyptian hieroglyphs draping down the center of her gown. Dressed in a reproduction of an Egyptian Pharaoh's headdress with black silk, feathers, and gold embellishments brushing up against Mary's ivory skin, she wears an imagined character of Queen Cleopatra. Lea Stephensen muses “the gown is mixing references to the Orient, with an 1870s silhouette. An ancient headdress, culminating in a blend of forms. Motifs from ancient Egypt physically wrapped around her corseted frame.” We can easily imagine Stevens gathering up her heavy skirt, rearranging her headdress, playfully lifting her hand with the fan, to adopt the semblance of the Egyptian. This, however, was not the only time that Mary sartorially embodied this Egyptian queen. In 1897, Mary dressed as Cleopatra for a second time for another costume event in London, photographed by John Thomspon (see figure 9).

Note how in both sartorial variations of the queen, Mary poses holding a fan made of feathers. Presumably, these are intended to resemble ostrich or peacock fans which show up on the inside walls of various Egyptian tombs discovered amidst archeological digs, including that of King Tutankhamun. 8

According to the Fan Museum of London, some of the earliest surviving examples of these fans would be resurrected in 1922 with the finding of the burial place of “King Tut.” However, more commonly found are those in relief form on the walls of tombs. To the ancient Egyptians, a single ostrich feather represented the Goddess Maat, who personified truth and the essential harmony of the universe. Ancient Egyptians used feathers for a range of purposes, the primary being to make fans. 9

Female members of the wealthy Anglophone world of the late nineteenth century were immortalized by painters and photographers in their couture-made, highly accessorized fancy dresses, “reinforcing the costume’s importance in fashion.” Images of women such as Mary, prove that interest in Egyptian-inspired fashions lasted up until the turn of the century. However, a taste for Oriental fashions of the wealthy New York elite was not limited to fancy gowns and costumes. Interest in historical fictionalized visuals of the Orient were reinforced by Parisian couture houses, reflecting an overall Orientalist current in the fashions of the nineteenth century.10

Underscoring the cultural significance of costume and dressing up among the rich, fashion publications often dedicated pages to “masquerade costumes.” These fashion plates can be found in both American and European publications, frequently appropriating oriental fashions. Alongside these spreads were illustrations displaying appropriate and fashionable everyday wear for the period. During this time, dictatorial fashion publications were the deciding factor for the mode of day. An issue of a French fashion publication widely disseminated in America called La Mode Illustree (Illustrious Fashions) from September 2, 1877, displays three fashionable female sitters, the woman furthest right, donning a scarf that has been wrapped around her hair, seemingly to resemble an Egyptian Pharaoh’s headdress (see figure 11).

Regarding Victorian and Gilded Age accessories, recognizable Egyptian motifs such as double-winged scarabs and the lotus flower enjoyed widespread popularity as well. An example of an 1880s chainmail bag which would have most likely been worn at the waist, attached to a Victorian woman’s chatelaine, lives in the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum of New York (see figure 12).

This orientalist current in the arts did not come to a halt with the Victorians. Egyptomania followed women’s fashionable dress through the turn of the century, directly into the introduction of modernism. Napoleon-inspired Egyptian fancy gowns of the Gilded Age and Victorians were replaced in the 1920s by ancient Orient-inspired flapper fashions and other accessories.

“Tutmania”: “Egyptianized” Flapper Frocks and Jewels

Post WWI, a spirit brimming with pleasure filled the air of the 1920s. After a stage of postwar economic uncertainty, a sense of relief was widespread. New dances such as the Shimmy, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, and the Charleston were performed by young men and women in speakeasies, as Prohibition had pushed people to conceal their drinking habits. The spirit of change was reflected in women’s fashions as new styles were required to keep up with the new, fast lifestyles lived by young women.

The mode of the day for the youthful modern woman was slinky, sheer, columnar sheath dresses, shimmering with bugle beads to be worn dancing after dark. Daytime wear for fashionable ladies reflected this trend with straight silhouettes that encouraged a boyish, straight shape, made of cottons and silks. The modern woman had decided that the days of the S bend and modest dressing were indeed over.

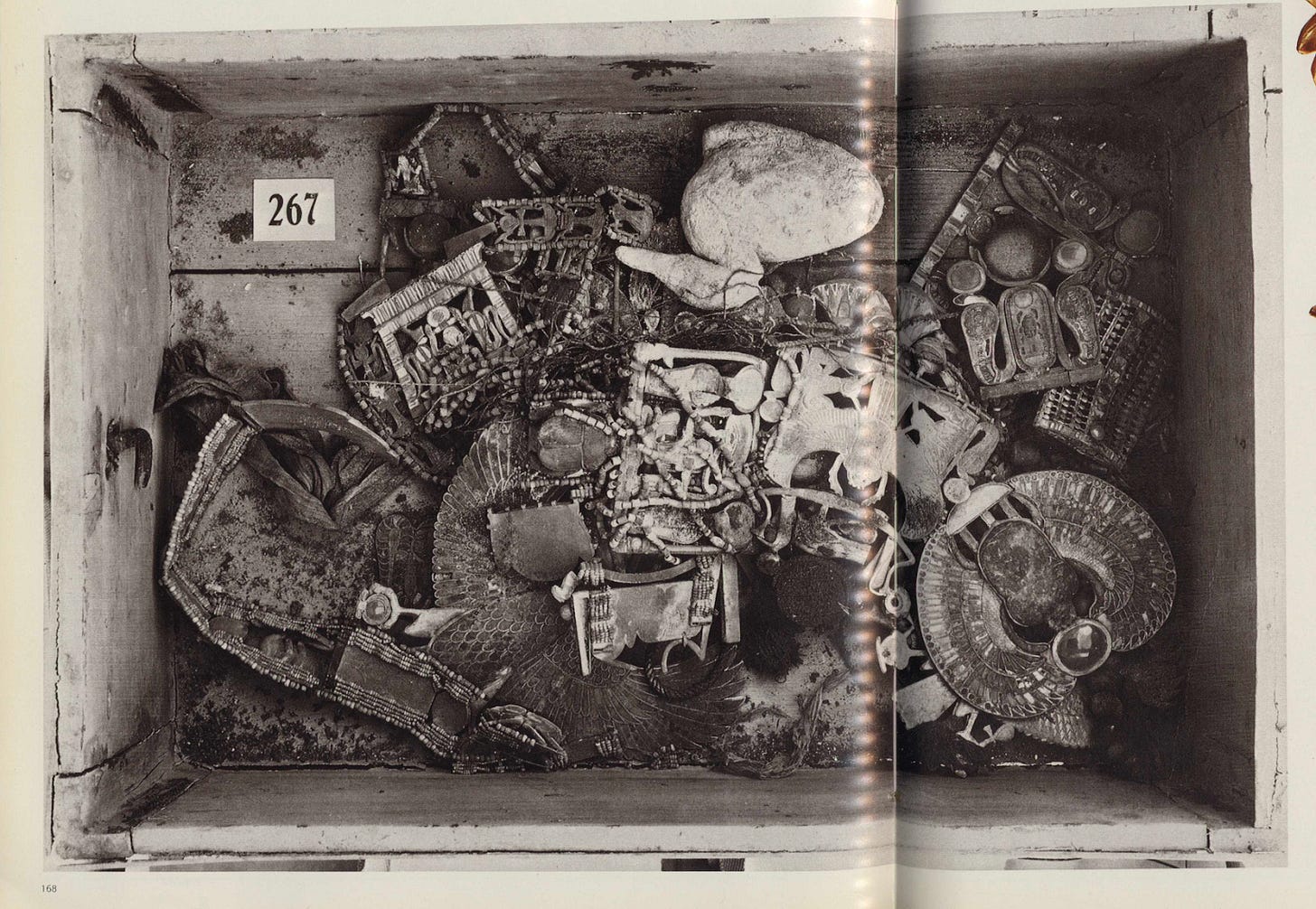

In 1922, the discovery and opening of King Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter gave yet another boost to the use of Egyptian motifs in fashion. Struck with “dumb amazement,” Carter described his findings as “Wonderful things!”: “strange animals, statues, and gold-everywhere, the glint of gold.” This treasure, a roomful, even “a whole museum full it seemed” - of objects were mostly the likes of which had never been seen by the Western world, piled upon one another with seemingly endless profusion.11

With over 5,000 objects, the items encased in the tomb included statues, gold necklaces in the shape of falcons and vultures, colorful breastplates depicting Egyptian gods, and both bracelets and rings adorned with scarab beetles. By far the most fascinating item found within this ancient tomb was the magnificent gold and blue coffin in which the king's body laid to rest.

Art Deco (known at the time as art moderne) had begun to make its rounds among different forms of visual arts around 1918-1919. However, this excavation can be attributed to the shift in deco motifs around 1923. Immediately, the fashion world became enamored by the images of Carter’s findings, quickly appropriating them. Almost immediately after this discovery, black and white, high contrast design motifs along with jewel tones inspired by Tut’s accessories began popping up. This included nearly-exact reproductions of Tutankhamen’s accessories, which saturated fashion publications and retail spaces. This early twentieth-century wave of Egyptomania across the West is known colloquially as “Tutmania,” named after the Egyptian king.12

An example of a Tutmania brooch residing in The Cleveland Museum of Art is shown in figure 16. This blue, black, and green brooch displays the use of Egyptian iconography being enjoyed by the famed jewelry design house Cartier. Some of the more breathtaking jewelry designs of the 1920s and 1930s were made by Cartier, post-discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun, in a style which we now refer to as Art Deco. Maison Cartier, according to historian April Calahan, were the progenitors of the Art Deco style in jewelry. 13

Faraway lands and widespread global influences captivated the designers Louis Cartier and Charles Jacqueau, defining the stylistic flair of the house: melon-ribbed emeralds from India, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, Nepalese coral dragons, and Egyptian pharaonic visage. The discovery of King Tut and the disseminated images of the tomb's treasures “prompted the appearance of lotus, scarab and pyramid shapes, along with subtle references to the stripes and curvature of King Tut’s headdress.” The house’s mixing of geometric shapes, high contrast, colored gemstones, Egyptian and Asian motifs resulted in a uniquely alluring, ostentatious, “Cartier look.”14

In "Design for a Scarab Bangle" (Figure 18), Maison Cartier combines elements of Art Deco such as the use of gold, and high contrast in combination with Egyptian iconography like the double-winged scarab. This design house’s influence on other makers of the time was extraordinarily impactful, meaning that their heavy use of Egyptian motifs spread like wildfire. Much of 1920s, and 1930s jewelry blurred the lines between being appropriative of ancient Egyptian visual culture, and being otherwise broadly Art Deco.

Instructing fashionable women to dress like “an Egyptian,” The July 1923 issue of The Sketch magazine advertised a range of on-trend, column dresses adorned with broadly Egyptian motifs, similar to those of the previously mentioned armchair attributed to Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Company (figure 2). If it weren’t for the blatantly obvious reference point, made clear by the title of this spread, “The Tutankhamen Touch,” people would most likely just consider this style “Art Deco.” This is a common thread among Egyptomania designs of this period, as Egyptian motifs and imagery, popularized by the discovery of King “Tut,” became assimilated into the visual cues of deco design.

Designer Jeanne Lanvin, renowned for her novel “Robe de Style” silhouette, enjoyed frequently incorporating watered-down Tutmania aesthetics into her design work. A 1926 example of her Robe de Style, housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, is fashioned from black silk, adorned with pearls and rhinestones cascading down the center front of the gown. The shape of the embellishments, appear to resemble the very end of a long, handsome feather of either a peacock or an ostrich.

Lanvin had previously more directly referenced Egypt with her 1922/1923 sea-side Biarritz collection entitled “Toutanhkhamen.” Madame Lanvin was said to have been a collector of Eastern textiles, drawing inspiration from them for her work.15

The Egyptian wave which had swept across the 1920s and 1930s with force slowed down through the mid-century. Although here and there, fashion brands continued to appropriate Egyptian motifs and aesthetics, it generally fell out of mainstream fashion. Realities of wartime in the 1940s were reflected in fashions of the day, and designers stopped taking as many risks, being required to adhere to strict war rationing. Designers during this period made safer, familiar design decisions, more frequently referencing the Western past versus that of the East. A primary example of this is the popularity of Christian Dior’s 1947 New Look, which reinterpreted the turn of-the-century S-bend look, with clean lines, and minimal ornamentation. However, this all changed in the 1960s as another wave of modernism swept through fashion.

Late Twentieth Century Fashionable High Artifice: “Egyptian” Cosmetics and Synthetics

The 1960s was marked by a range of political and social tensions impacting people across the Western world. In 1961, the space race was escalated by the technological competition between the US and Russia as Yuri Gagarin orbited Earth, becoming the first man in space. In 1962 America entered the Vietnam war, which would not end until 1975. The following year in 1963, JFK was assassinated, as well as civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. In 1969, the Stonewall Rebellion in New York City catalyzed the gay rights movement. The latter half of the decade also saw anti-war sentiment growing among student populations in America, Europe, and Canada, who took their anger to the streets by protesting. All of these events resulted in a sense of instability and as always, general political unrest meant a widespread desire for escapism and fantasy.

Also, the latter half of the century saw a seismic explosion in a range of subcultures around the Western world, resulting in subcultural fashion elements being appropriated by high fashion designers. For the first time we were no longer witnessing fashion “trickle down,” rather it was “trickling up.” This change in the structural integrity of the industry along with a newfound priority for individualism among young people, was referred to by Diana Vreeland of Vogue in 1965 as the “Youthquake.” Many of the styles worn by these “youthquakers” were made of highly novel, synthetic materials. Mary Quant’s mini skirts, space-age PVC, swinging colorful tights, and baby girl Mary Janes, were popular among women and adolescent girls. Their male counterparts wore bright colors, and flamboyant patterns via Mr Fish in London, and other boutiques in major cities. The world called for an escape, and fashion provided! With the introduction of a range of synthetic materials and textiles in the latter half of the twentieth century, Egyptomania trends reflected this high-artifice: with completely historically inaccurate, fabricated versions of Egypt.16

The 1960s saw a major growth in the popularity of television, media contributing strongly to popular trends in fashion and beauty. By the 1960s, Egyptomania had taken the West once again by storm, in part due to the release of the 1963 film Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth (Liz) Taylor. One of the results of this film was a brief fad for “the Cleopatra Look” characterized by dark eyeliner (already made trendy by model Twiggy) and brilliantly bright blue eyeshadow. Liz Taylor’s portrayal of Cleopatra in the 1963 film, with makeup done by Guiseppe Manchelli, “brought bold eye makeup to the forefront of beauty, and brands such as Revlon began to develop Cleopatra-inspired products.” Figure 24 displays a cosmetics advertisement for Revlon from the year 1965, selling a lip shade named “Sphinx Pink” and a coordinating eyeshadow palette on theme as well, called “Sphinx Eyes.”17

Hintings of postmodern dress began to emerge through the fashions of different subcultures in the 1960s, many of whom took inspiration from past decades, and Eastern cultures. The wide range of subcultural dress was appropriated by boutique designers such as Besty Johnson of Paraphernalia in New York, and Barabara Hulanicki of Biba in London. Late 1960s Eastern-inspired fashions were all the rage at music festivals such as the first Woodstock fest in Upstate New York on August 15th, 1969. Fashion historian Raissa Bretaña muses that the interest in wearing garments and textiles deemed as “exotic,” in part stemmed from a desire to appear [well-traveled], or knowledgable about Oriental cultures (Bretaña Raissa, “personal communication.” April 17, 2024). Many of the religions that the Hippies practiced (whether authentically or not) were derived from the Eastern world. With young people rejecting the traditional, conservative Western ideals of their parents' generation, many felt closely tied to the beliefs of religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism. As well as making nods to other cultures, designers more broadly enjoyed taking inspiration from past decades. Sometimes, these two things coalesced, which is certainly an explanation for this wave of late twentieth-century Egyptomania.

Another primary reason for the renewed fascination with Egypt was the travelling museum exhibition entitled The Treasures of Tutankhamun which made its rounds among six American museums between the years of 1972 and 1981 (the exhibition opened at the MET on December 15, 1975). The King's golden burial mask was among the approximately 55 objects on display, which prompted an even stronger resurgence in a general interest in ancient Egypt. To pair with Egyptian-appropriated fashions of the 70s, jewelry designers created near-exact reproductions of sparkling jewels found in the exhibit. A necklace depicting the vulture of the Egyptian god Nekhbet was especially popular among jewelry designers in the 1970s.18

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan also sold reproductions of jewelry items found in the exhibition in their gift shop. Along with this, they also offered pillows, puzzles, calendars, eyeglass cases, and other trinkets, making it possible for museum visitors to bring a piece of the exhibition home with them. Figures 29 and 30 display pages from the exhibition catalogue.

Artisans at the MET also “adapted, sized and equipped [reproduced] objects to make them amenable to modern wear and display” as an interactive element of the exhibition. Harping back to Lady Arthur Paget in her 1875 Cleopatra costume: Lea Stephenson says “Haptic moments link possessor and decorative, leading to a sensuous interaction.” 19

These tangible experiences with Egyptian antiquity made possible through designers, artisans, and museum curators alike, aid in bridging the gap between the historical and the contemporary person, sparking a sensorial, emotional engagement with other far-away cultures. The sartorial conversation regarding appropriation versus appreciation which comes up with every new fashion season is certainly highlighted by all of these examples. Some of which, eg. Cartier could be written off as aesthetic appreciation, whereas more overtly orientalist designs like fashions of the 1920s and Victorian “masquerade costumes” are dangerously appropriative. The violent current of the West’s obsession with swiping elements of Eastern material culture continued through the twentieth, and into the twenty-first century.

In 2023, The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) exhibited Egyptomania: Fashion’s Conflicted Obsession. By placing twenty-first-century and ancient objects in conversation with one another, they interrogated and explored this ever-evolving complicated fascination. The assistant curator at the CMA, Darnell Jamal-Lisby, asserts that the primary reason for the West’s long and tangible obsession with Egyptian aesthetics, which he claims dates back to antiquity, is due to the diverse nature of the populus of ancient Egypt. The foundational society of Egypt was an indigenous African people who first appeared in the southern Nile Valley (Upper Egypt) by 4500 B.C.E. and spread northward to Lower Egypt. 20

The Brooklyn Museum explains how joined over five thousand years by other Africans from Nubia and Libya, as well as Semites, Persians, Greeks, and Romans, “their distinctly multicultural society produced an astonishing array of objects and structures.” This range of cultures within Egypt was brought together through a shared polytheistic religion. Due to Egypt’s many trade relationships with other Eastern lands, we can see the permeating of ancient Egyptian visual culture along the Mediterranean as early as around 3200 BC. One may argue that this very early interest in Egyptian culture could be considered an example of ancient Egyptomania.21

To what extent does this obsession reflect the broader colonial nature of the Western world? The enduring fascination with Egyptian culture and aesthetics can underscore how deeply these elements have been embedded within the visual and cultural lexicon of the West. Some of the most highly regarded couturiers and design houses (think Paul Poiret, Maison Cartier, John Galliano, etc.) works’ are highly orientalist in nature. Use and appropriation of Oriental design elements for many Western designers, is literally a house-code. This long-standing interest cannot be disentangled from the colonial frameworks which have historically driven appropriation, reinterpretation, and the commodification of Egyptian art and symbology.

The machine of Hollywood also cannot be left out of this conversation, as it has greatly contributed to multiple waves of Egyptian revivals, as well as reshaping our cultural understanding of Egypt as a whole. Out of the many tales of Kings, Queens, and Pharaohs of antiquity, Cleopatra reigns supreme in the consciousness of Hollywood storytellers. Many iterations of the story of Cleopatra have been produced by Hollywood beginning with Cleopatra (1917) starring the vampy Theda Bara which was tragically destroyed in 1937 by the infamous FOX studio fire along with a vast majority of films from the silent era. In 2023, a man in the United States purchased a listing for a 1920s toy film projector, where he discovered the only known clip of the film. He posted this 40-second shot on Youtube which has become the only real proof (to the general public) of its existence.

Other variations include: Cleopatra (1934), Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), Two Nights with Cleopatra (1954), Cleopatra (1963), and Antony and Cleopatra (1974). These films are just a few within the large repertoire of on-screen retellings of the Queen of the Nile. The second part of my research into sartorial Egyptomania will look at how two costume designers have used Egyptian symbology and design motifs in their on-screen depictions of Cleopatra, thirty years apart. As you do your vintage shopping, make sure to keep an eye out for scarab beetles… once you see it, you won’t be able to unsee it!

Rosenberg, Jennifer. “The Full Story of How King Tut’s Tomb Was Discovered.” ThoughtCo, January 10, 2021.

“Description de l’égypte.” Wikipedia, October 3, 2024.

“The Egyptian Revival Gateway.” Mount Auburn Cemetery. Accessed December 18, 2024.

Stephenson, Lea. “‘Dressing Up’ Egypt: Performing Race and Late 19th-Century Egyptomania.” YouTube, February 29, 2024.

“Harper’s Bazaar 22 January, 1870, p.55.” New York, n.d. Accessed December 18, 2024.

Yalman, Suzan. “The Art of the Mamluk Period (1250–1517): Essay: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, January 1, 2001.

Campagnol, Isabella. Style from the Nile: Egyptomania in fashion from the 19th century to the present day. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword History, 2022.

“The History of Fans: The Fan Museum, Greenwich.” The Fan Museum | Celebrating the history of fans & the craft of fan making, April 6, 2022.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo. “Ostrich Hunt Fan of Tutankhamun.” Egypt Museum, December 21, 2023.

James Cole, Daniel; Deihl, Nancy. The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 (p. 94). Quercus Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Via Style from The Nile: Egyptomania in Fashion (From the 19th Century to Present Day)

Elliott, Amy. “Cartier: The Jeweler Who Helped Define Art Deco.” The Study, November 22, 2022.

Zachary, Cassidy, and April Calahan. “Egyptomania: Fashion’s Conflicted Obsession, an Interview with Darnell- Jamal Lisby.” Episode. Dressed: The History of Fashion, August 8, 2023.

Elliott, Amy. “Cartier: The Jeweler Who Helped Define Art Deco.” The Study, November 22, 2022.

Merceron, Dean, Harold Koda, and Alber Albaz. Lanvin. New York, New York: Rizzoli, 2007.

James Cole, Daniel; Deihl, Nancy. The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 (p. 94). Quercus Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Karchin, Lindsay , and Delphine Horvath. "A Brief History of Makeup." Cosmetics Marketing: Strategy And Innovation In The Beauty Industry. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023. viii–33. Bloomsbury Fashion Central. Web. 21 Nov. 2024

The Treasures of Tutankhamun Exhibition Catalog.” Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections, 1978.

“The Treasures of Tutankhamun Exhibition Catalog.” Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections, 1978.

“Search the Collection: Cleveland Museum of Art.” Home. Accessed December 18, 2024.

“Ancient Egyptian Art.” Brooklyn Museum. Accessed December 18, 2024.

The link between what we see as just “art deco” design and it’s true Egyptian inspired elements is so fascinating!! It’s so subtle, it’s easy to miss if you aren’t looking. You’re right I won’t be able to unsee it. As a kid who used to check out a book about mummies every month from my elementary school library, I am finding this fascinating! Can’t wait for part 2!