Egyptomania in American Cinema! (Installment #2)

Miss Claudette Colbert STUNS as sensual Queen Cleopatra in 1934 film by Cecil B. DeMille! Oh, and Liz Taylor is there. Film spoilers and copious amounts of scarabs ahead...

Welcome to installment two of my Egyptomania series! In this part, I will be looking at the costume design of two on-screen tellings of the story of Queen Cleopatra. In the midst of my research process, I took a trip with my sister to Toronto for a Taylor Swift concert. If you are wondering, this was one of the best nights of my life (no sarcasm). We stopped for dinner with family the day before, and I found myself looking at my Nonna’s old Singer sewing machine. This is when I realized that this sewing table has been in their home for my entire life and it took me 21 years to notice that it was covered in gold lacquered visage of Egyptian pharaoh heads. A spool of black thread, perched upon an immortalized golden god. Since diving head first into Egyptomania, I have begun to see it everywhere. Designs from the periods aforementioned in my previous post (1920s, 1970s, etc.) are all screaming at me in misinterpreted hieroglyphics.

This version of the Singer was originally produced in 1890 (Victorian revival), as well as being reproduced both in 1910, and 1924/28 (“Tutmania”). I believe this flawlessly underscores the cultural influence of these design elements. Not only did clothing reflect “Egyptian” influence, but so did the machines which created these garments. People could produce fantastical versions of “Egypt” through at-home projects with a sewing machine enveloped in effigies of Egyptian gods. Singer reproduced this machine in 1973 as well, in the wake of the travelling King Tut museum exhibition. My Nonna told me that she bought it at a garage sale for $20 because it reminded her of the one that her mother (my great Nonna Adele) used to sew their clothing with.

WARNING: film spoilers impending. If you are not familiar with the story of Cleopatra, you will be after this. I can say for certain that you can go without seeing the 1963 adaptation: stick with Claudette Colbert and ditch Liz Taylor (sorry Liz fans, the movie sucks, and is three hours too long).

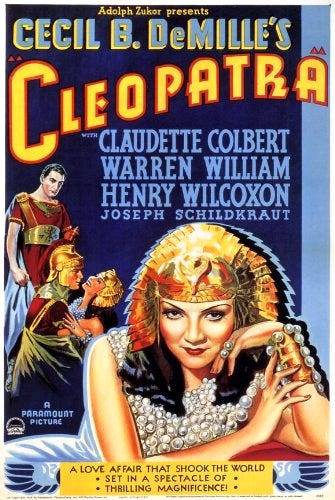

Cleopatra (1934) is directed by Cecil B DeMille and stars Claudette Colbert as Queen Cleopatra. Writers credited for the film are Waldemar Young, Vincent Lawrence, and Bartlett Cormack. The film was distributed by Paramount Production Inc. with costume design by the great Travis Banton.

Similar to the film's predecessor, Cleopatra (1917) starring the vampy Theda Bara, DeMille tells the heart-wrenching story of the Roman-Egyptian queen whose wicked sexuality is consistently made an essential element of the plotline. Early in the film, Cleopatra is displayed to Caesar by being dramatically rolled out of a carpet, portrayed as primarily an object of his affection and desire. The story classically ends with Queen Cleopatra ending her life via snake bite.

Film #1: Cleopatra (1934)- Costume Design by Travis Banton

Travis Banton is considered by many to be one of most accomplished costume designers of twentieth century Hollywood. He is well known for his long-time professional collaboration with Marlene Dietrich whose name readily conjures the grandeur of Hollywood’s “golden age” with her sophistication and allure. Banton’s work is in part to thank for the Dietrich dyke swag, and has been both referenced and reinterpreted by designers over the years. 1

Banton famously designed the costumes for Dietrich in Morocco (1930) which includes one of the first on-screen lesbian kisses. In the tradition of many young creative minds, he moved to New York City to attend school where he studied art and fashion design at both Columbia University and the Arts Student League of New York. Early in his career he earned his fame when Mary Pickford wore one of his designs in her wedding to Douglas Fairbanks.2

About the Design by Banton

The entirety of this film is a 1930s Hays-Code-abiding Hollywood fantasy of the Orient, filled to the brim with gold lamé and bias cut silks. Colbert has quickly become one of my favorite classic Hollywood faces. She is wonderfully expressive in a very-1930s way, which is most likely the result of her time as a silent film actor. As Queen Cleopatra, Colbert is charming and sultry with stick thin, rounded brows and kohled eyes.

Author and film/fashion historian Robert LaVine said of Colbert’s Cleopatra: “Of the numerous films that portray the life and loves of Egypt’s Cleopatra, perhaps none was as visually extraordinary as that produced and directed by Cecil B. De Mille for Paramount in 1934.” As the “serpent of the Nile,” Colbert dons a range of pseudo-Egyptian, skin-baring, slinky costumes. After watching the film, I believe that Banton’s designs intended to make reference to Western Egyptomania motifs, while remaining true to the fashionable mode of the mid 1930s. He accomplishes this through textile choice, handsome use of ornamentation, and other design elements such as novel fabric cutting techniques like the bias cut.3

The second costume that Colbert is seen wearing on screen consists of a two piece black and silver lamé Egyptian-inspired gown. The ensemble is made of a chain-halter-wrap bodice attached to a silver and black flying scarab with a floor-length skirt. The long, slithering train is ornamented both at the waistband and center back seam with embroidery of black, silver and blue beading.

The use of silk lamé feels aligned with Robert LaVine’s description of Colbert as “serpent of the Nile.” It is difficult not to be taken by the snake-like movement of the bias cut lamé as she exits the room in the final moments of the scene. The tail end of her dress catches the light wonderfully as a snake's skin would. The viridescent silk, slithering across the floor of Caesars palace, could arguably be sartorial foreshadowing for the queen's self-induced serpentine demise.

At the front center of her waist, as well as center of her collar bone, sits two scarab-beetle-shaped embellishments. I told you we’d come back to scarabs (spoiler- they are everywhere). The Egyptian scarab has frequently been used, carefully set on a pair of double wings, by designers in the era of art deco interested in making reference to Egypt. Darnell Jamal-Lisby examines in his 2023 CMA exhibition how ancient Egyptian jewelry helped provide spiritual protection in life and death, most notably scarab amulets, which represent “Khepri, the early morning sun god connected with resurrection.” Presumably the spiritual meaning of the beetle was most likely unknown by Banton. However, the scarab would have been easily recognizable by the fashionably inclined as an “Egyptian” motif, understood by viewers of this mid-1930s film.

Later in the scene, atop this striking gown, the queen dons a shawl which appears to be a Hollywood reinterpretation of an Egyptian Assuit (Asyut) textile. The very same as the one I was introduced to for the first time at the vintage shop! This garment made its rounds among the Western world beginning in the late nineteenth century, as both individual travelers such as the art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner and colonial empires like Napoleon's army brought these textiles back as Egyptian treasures, proof of their time on the Nile.

This netted fabric is commonly made of cotton or linen and embroidered with metal, accomplished by threading wide needles with flat metallic strips about 1/8” wide. The textile gets its name from its birth place, the Asyut region of Upper Egypt where it is produced by locals. First imported to France for the Chicago Exposition in 1893, it experienced a resurgence in popularity during “Tutmania.” The metal motifs were well suited for the Art Deco style which reigned in popularity at the time of the film, which would also make sense as to why Banton chose to include his glammed-up reinterpretation.

In the melodramatic scene where Cleopatra is told that Julius Caesar has been killed by the Roman senate, I believe Banton could be making reference to French design house Callot Soeurs. In 1930 the house designed their famed cathedral length wedding dress, which now resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and was the finale of their most recent Costume Institute exhibition entitled Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion. I saw this dress on display back in the spring at the MET and found myself taken by the scale of the dramatic silk train. According to the museum’s website, with its silk scalloped train cut on the bias, it perfectly illustrates the “sleek, reductive look of 1930s fashion.” I agree with this assessment. The rippling effect created by the scalloped edge resembles the movement of water, possibly that of a Japanese landscape, would be consistent with the house’s use of Asian motifs as design inspiration.4

Similarly to Banton, the house looked to Oriental landscapes to successfully create design fantasy for westerners, once again underscoring the Orientalist nature of late nineteenth and early twentieth century fashion design, as reflected on screen. Whether Banton’s ensemble for Colbert is a direct interpretation of this French design, it certainly is of its time. With its considerable train resembling wedding attire of the mid 1930s and utilization of the bias cut technique, it feels representative of the period’s allure and excess. Cleopatra, who was presumably planning on marrying Caesar, may have also been put in a matrimonial ensemble to emphasize her heartbreak in this scene.

It would be impossible to assess costumes in a film portraying the Egyptian queen and ignore her wide range of headpieces which are the defining factor of Hollywood's “Cleopatra look.” Every version of the queen, fabricated by directors, costumers and actors, has donned some variation of barely-Egyptian headwear. Some of these pieces have been created referencing ancient source material, while others are just solely Egyptian revival ornaments that steal aesthetics from different eastern cultures, resulting in a generally romantic, mystical, “Oriental” look.

Colbert dons a metal headband, which wraps around the back of her head and drapes down the center of her forehead, ornamented with three scarab pendants. Based on my assessment of images of ancient headdresses held in museum collections, this design does not appear to resemble Egyptian antiquity. Banton relies once again on the addition of the trifecta of scarab beetles to encourage the association with Egypt. However, it certainly is quite similar to 1920s Egyptian revival headpieces popular in the decade prior.

Figure 18 displays an enamel and freshwater pearl headpiece sold online by Demetra Vintage which dates to around 1925. This piece is quite similar to the silhouette of Banton’s design for Colbert, making this look once again historically and culturally inaccurate however, fashionable for the time.

Other headwear worn throughout the film appear to be based on historical images of Cleopatra in relief form. The metal headpiece worn by Cleopatra in the final scene where she is killed by a venomous snake, has similar design elements to that worn by the real queen depicted in figure 20 and 21. Both Colbert, and the real Egyptian queen’s crowns have a snake jutting out of the front, two horn-like structures erupting from the top, as well as the wings of a bird on either side of their faces.

Regarding hair and makeup for this film, there is not much to say except for the fact that it is certainly of its time (that is the 1930s…not antiquity). Claudette Colbert wears penciled on eyebrows, kohl which drags the corner of her eye outward, as well as a dark lip. This makeup look was extremely popular at the time of the film, and doesn’t feel “Egyptian.” The consistent application of 1920s makeup throughout the entirety of the film provides an undistracting diversion from historical accuracy, as there are no looks that feel historically salient and thus suspend the viewer between modernity and antiquity. Banton’s Cleopatra is one of the earliest onscreen depictions of an ancient Egyptian which imposes western beauty ideals onto the Orient.

Film #2: Cleopatra (1963)- Costume Design by Irene Conley

Cleopatra (1963), described by the press as “The motion picture the world has been waiting for!” was directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, starring Elizabeth (Liz) Taylor as Queen Cleopatra, Rex Harrison as Julius Caesar and Richard Burton as Marc Anthony. A list of people according to IMDb are credited with makeup, a few names being Alberto De Rossi, Giuseppe and Mario Banchelli. The film was produced by 20th Century Fox in collaboration with Walter Wanger. This lengthy, four hour and eleven minute film was nominated for nine Academy Awards, winning four: best cinematography and art direction, set decoration and color, best special visual effects, and best costume design. This movie is a major aesthetic, technical feat in the realm of set design, hair, makeup and costume. Costume design worn by Liz Taylor throughout the film was executed by Irene (Renie) Conley.

Renie studied design at the Chouinard Art Institute and the University of California in Los Angeles. She began her design career working on theater sets, eventually becoming a sketch designer for Paramount Pictures. In 1937, she became a costume designer for RKO pictures where she remained until the 1950s when she transitioned into freelance work. She designed costumes for the films A Date With a Falcon (1942), and The Falcon and the Co-Eds (1943). Her work on the 1963 Cleopatra is considered one of her major career milestones, earning her an Oscar for costume design.

About the Design by Renie

Similarly to Banton’s designs for Colbert, for some ensembles Renie utilized fashion trends of the day, incorporating an “Egyptian” flair, in order to sell the story of the queen. In others, she created noteworthy, historically influenced looks through use of a range of Egyptian symbols and motifs. Aside from this, I believe that she also was attempting to remind the viewer of the queen's Greek bloodline, something less present in the 1934 film. The most striking element of many of the designs she created for Liz Taylor are the particularly sumptuous jewels and her many gold lacquered garments.

The most dramatic, and arguably most notable costume from the entire four hour lackluster performance given by Taylor, is the ensemble she wears as she is carried into Rome by an army of men. Pictured in figure 24, the queen wears a 24 karat gold dress and cape, which appears to be assembled from thin strips of possibly gold leather, embellished with seed beads, bugle beads and anchored sequins. 5

This scene depicts a lavish procession intended to showcase the queen’s beauty and power to both the Roman people and Caesar himself. Renie and her team certainly accomplish this level of drama through wonderfully ornate ornamentation. An example of this is the queen’s golden cape that was presumably designed to resemble the wings of a phoenix or a falcon. Birds are frequently found among other Egyptian iconography. Motifs used in ancient Egyptian jewelry are most often figures of gods, planets, or other abstract forms. The falcon was used to represent multiple ancient Egyptian goddesses, including the sky goddess Nut and Nekhbet. Renie was most likely looking to ancient source material, possibly jewelry found in King Tut’s tomb as a reference point (see my previous post).

In this look it is certainly evident that Renie was referencing Egyptian antiquity. The red crown, in ancient Egypt, was worn by rulers of Lower Egypt. In relief, gods and goddesses are sometimes depicted wearing this crown in order to associate them with the role of the king, and the ruler's divine right to the land. The white crown was worn by rulers of Upper Egypt, similarly symbolizing power over the land. The double crown was a combination of the red crown of Lower Egypt and the white crown of Upper Egypt. The headpiece worn in this scene appears to be Renie’s interpretation of the double crown of ancient Egypt (depicted in figures 24, 25, 26).

When it comes to this queen's head dresses, I believe that Renie was also interested in heightening the drama of the story with accessories. Red is not a color commonly associated with ancient Egypt, however is associated with Roman dress, and more broadly neoclassicism. It is established early in the film that Cleopatra is aligning herself with Rome through her romantic pursuits; much of the non-armor costumes donned by Roman soldiers are designed in red.

This golden sheath dress, nipped in at Liz Taylor's waist line is one of various designs from the film evoking a sense of early twentieth century neoclassicism. Renie seems to have been inspired by the Queen's primarily Greek ancestry; Cleoptra belonged to the Ptolemaic dynasty, a Greek Macedonian family who after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt in 332 BC, established themselves in the land of the Nile.

The texture of this dress is highly reminiscent of the accordion pleating technique pioneered by Spanish fashion designer Mariano Fortuny in creating his renowned Delphos gown, originally in 1909. He is well known for his novel micro-pleats, however more broadly for being one of the pioneers of the early twentieth century wave of neoclassicism in fashion design. Fortuny’s wife, Henriette, however not frequently mentioned in history books was the co-designer of this design technique. Delphos being their signature design, takes its name from the ancient Greek sculpture, the Charioteer of Delphi. The dress is a sleeveless column, pleated in Fortuny’s exclusive micro-accordion method, trailing evenly around the front, back and sides of the wearer, achieving the look of an inverted morning glory blossom.6

When Cleopatra is seen standing, her dress falls similarly in the shape of inverted flora. This gown looks as if Renie took a Fortuny dress and lacquered it in liquid gold leaf, once again making the queen appear highly lustrous. This design could possibly be based on a Fortuny design similar to the one that lives at London’s Victoria and Albert museum (figure 29). Whether it be her intent or not, the association of Greek and Roman antiquity with neoclassicism in the arts certainly encourages this association with the queen. Figure 30 pictures another look by Renie which is broadly inspired by antiquity. The cream toned asymmetrical dress feels highly reminiscent of a Greek Chiton.

Cleopatra’s hair in this scene, as well as in many others throughout the film is angular and black (figure 30, 32). Different variations of similar hairstyles are used throughout the film which appear to be vaguely based on images of ancient Egyptian’s who wore their hair in braids that formed a style similar to modern day bangs. As CMA curator Darnell Jamal-Lisby stated, ancient Egypt was made up of an indigenous African population who historically, braids are associated with. Men and women of ancient Egypt can be commonly found in relief wearing this hairstyle, which has its origins in African culture dating back to 3500 BC. This is one of the more egregious examples of appropriation in this film, as Liz Taylor is a British American white woman. This is also one of the major differences between Cleopatra (1934); hair and makeup attempt to be influenced by historicism. However, not all looks were based on ancient Egyptian styles, as in other scenes Cleopatra wears straight back extensions or a timely 1960s voluminous updo. 7

At some point in the second half of the film, there is a major departure from primarily ancient Egyptian and Roman inspired fashions, and looks start to feel true to the reigning styles at the time of filming. There is a scene where Cleopatra is at home, and wears a white jumpsuit along with a navy blue robe that feels modern and out of place in the story. I guess one could argue the neoclassical influence on the color and shape of the suit, but I think it appears much too contemporary, pulling the viewer out of the story.

Makeup in this film is consistent, as Liz Taylor is primarily in a bold blue eye with extra thick, dark eyeliner. This is certainly informed by images of ancient Egyptian women in relief as depicted in figure 33 with a “cat eye.” This makeup seems to be informed by images of antiquity, however not by Cleopatra herself. The blue color could possibly be remnants of the eighteenth century trend for “Egyptian” colors such as the popular shade of teal-green called Scarabée.

So now we know the origins of fashionable western Egyptian revival styles, and have seen how these fashions have been filtered through film. I hope you’re still with me! I think one of the most interesting about this phenomenon is how much further we seem to get from accuracy with each design: Artifice builds upon itself. There’s one more to go: a discussion around late twentieth and early twenty first century sartorial Egyptomania. Spoiler: John Galliano makes himself very present in this conversation (shocker). If you are too impatient to wait for installment #3, watch the Dior A/W 2004 collection designed by Galliano (talk about artifice and appropriation). I also encourage you to watch these films and see what else stands out to you, I’m sure there are things I missed with my one time viewing. In the mean time, keep an eye out for Egyptian Singer machines in your grandmothers home!

Bretaña, Raissa, Ira M Resnick, and Jane Fonda. Moxie: The Daring Women of Classic Hollywood. Abbeville Press, n.d. Accessed December 18, 2024.

“Travis Banton.” Wikipedia, November 26, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Travis_Banton.

LaVine, W. Robert, and Allen Florio. In a glamorous fashion: The fabulous years of Hollywood costume design. London: Allen & Unwin, 1981.

“Callot Soeurs: Wedding Ensemble: French.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 1, 1970. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/156001.

Woodward, Daisy. “Top 10 Facts about Cleopatra’s Costumes.” AnOther Magazine, July 12, 2013.

James Cole, Daniel; Deihl, Nancy. The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 (p. 253). Quercus Publishing. Kindle Edition.

“Historical Significance of Black Hairstyles.” Illinois State Board of Education. Accessed January 9, 2025.