Final Notes on High-Fashion Egyptomaniacs (Installment #3)

Cleopatra’s influences on contemporary fashion, film history, and significance within broader western popular culture.

Cleopatra (1934) and Cleopatra (1963) are just two within a larger collection of Hollywood interpretations of stories of the ancient orient created to entertain westerners, encouraging them to view this land those who inhabit it, through their romantic, exoticized lens. Many other versions of the story of Cleopatra exist including Mark Antony and Cleopatra (1913), Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), Two Nights with Cleopatra (1954) and Antony and Cleopatra (1972), just to name a few.

Cleopatra (1934) solidified the image of the Egyptian queen as a seductive, fashionable femme fatale. According to Women’s Wear Daily in August 1934, the film had already begun to influence women’s fashion trends immediately after its release. The publication advertised “modern versions of the costumes worn in the production” designed by Travis Banton himself;

“Celanese satin is used for the evening gown, in deep pansy blue, with a jeweled collar reflecting the Egyptian influence; the other dress, a hostess type, in tunic outline, is in raspberry crepe, and has a scarab motif at the throat and wrists.”

The almost-nude styles worn by Colbert also gave way to a new interest in revealing on screen costumes in the age of the Hays Code. The same 1934 issue of WWD, reported “Cleopatra suggests new extremes in Nudity for costumes!” The article describes how Banton’s designs were shown to members of the fashion group in New York at the Waldorf Astoria pre-release, giving them plenty of time to make their impact on everyday women’s fashions. WWD also notes how Banton’s designs “based on historical data… might well give inspiration for modern evening gowns.”

The sartorial legacy of Liz Taylor’s Cleopatra is primarily found in contemporary makeup looks inspired by the film. Almost immediately post-release, as proven by Revlon's advertisements instructing women on how to get “the new Cleopatra look”, Banchelli’s bold-eye glam was highly influential (see figure 24 installation #1). More recently, Alexander McQueen’s Autumn/Winter 2007/08 Ready to Wear included themes of witchcraft, paganism, and religious persecution, sending models down the runway looking like Taylor. When asked about the inspiration behind the glam, makeup artist Charlotte Tilbury answered plainly, “the look today is Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra.”1

A 2007 limited edition collection of MAC cosmetics featuring shades named “Nile” and “Pharaoh” developed from the catwalk looks dreamed up, and executed by Tilbury.2

As well as this, the 1963 film inspired a range of products sold by retailers such as Selfridges hats, Dolcis sandals, Providence jewelry and McCrory’s hair curlers, just to name a few. This movie produced during the age of 50s and 60s grand Hollywood epics, inspired an Egyptian themed LIFE magazine editorial, praising the Cleopatra effect, “referencing a Madame Gres collection in Paris… to add an air of European authority.”3

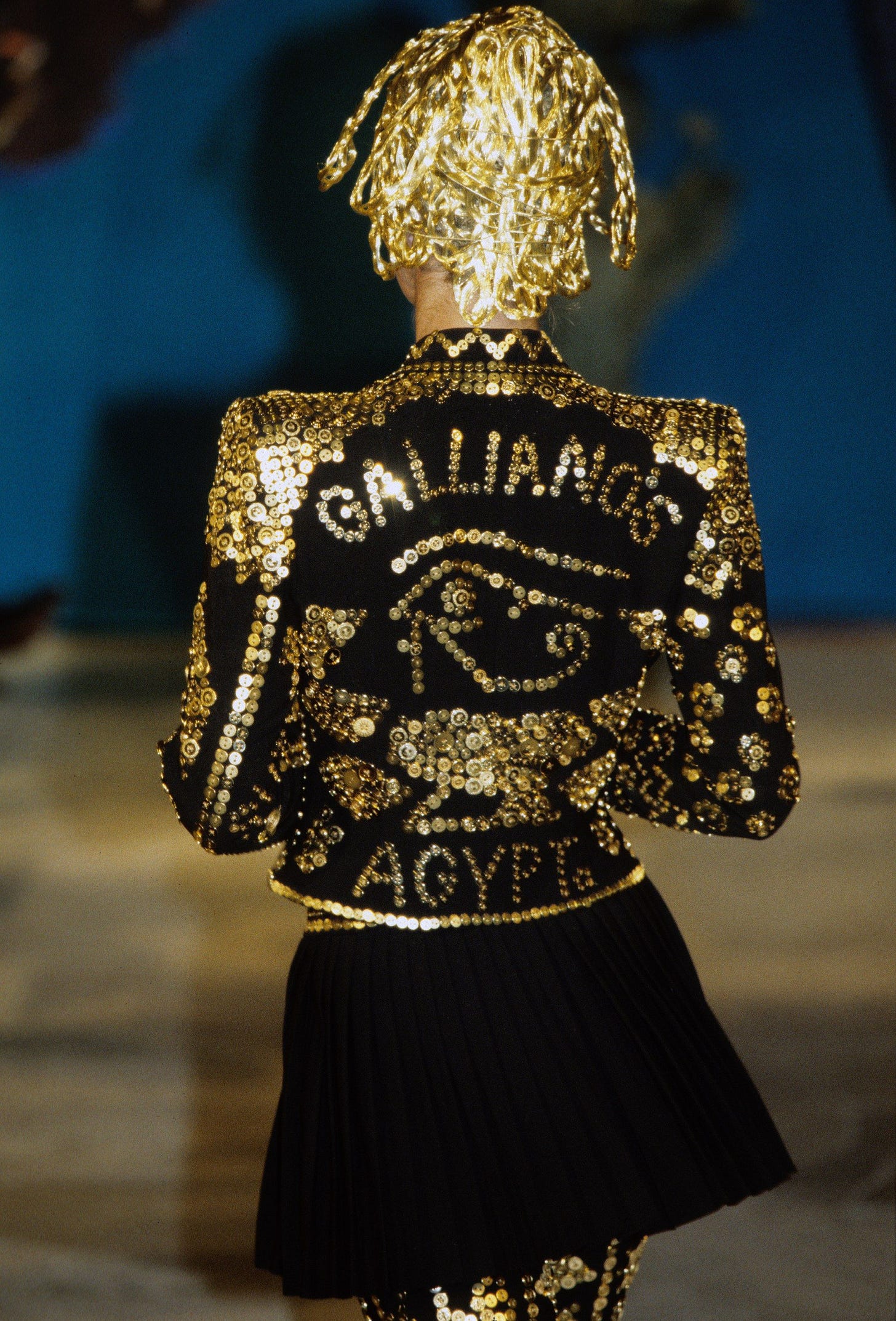

Speaking more broadly, these films are a part of the larger repertoire of those depicting Egypt from the perspective of Hollywood storytellers, and have influenced a range of contemporary designers. John Galliano has done multiple collections in which he makes unmistakable orientalist nods at Egypt, or rather the version fabricated by the western film industry, such as in Galliano’s Spring 1997 collection, as well as Dior Spring 2004.

Chanel’s Métiers d'Art 2018/2019 collection designed by Karl Lagerfeld was described by Vogue as “a spoof on ancient Egypt as seen through the eyes of Hollywood,” and it’s look as “Cleopatra meets Sid and Nancy, complete with trompe l'oeil tattoos and a jewel-of-the-Nile dress made entirely out of safety pins.” This collection was essentially a punked up Liz Taylor with its references to the silhouettes of the 1960s.

Cleopatra (1963) almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox with a ballooning budget including Liz Taylor’s record high fee which differs depending on the source; most report $1-5 million. Taylor also required 65 outfit changes over the four hour span of the film; “though accuracy may be flawed, the opulence is a feast for the eyes.”4

The estimated total costs came to approximately $31 million, becoming the most expensive film ever made up to that point, nearly bankrupting the studio. Cleopatra became the highest grossing film of 1963, and one of the highest of the decade, worldwide.5

Closing Remarks re: On Screen Egyptomania

The flamboyant couturier and costume designer of the early twentieth century, Paul Poiret, according to author Robert LaVine, “revolutionized fashion by bringing a new form of beauty, steeped in orientalism, to women.” Poiret is known by many as one of the primary designers who “modernized” western women’s dress. His romantic, free-moving, eastern-appropriated designs enchanted the fashion world so greatly that costume designers began to reference his work for on screen and stage performances. He created ankle tight hobble skirts, minaret-shaped tunics, draping women's heads in striped silk turban’s sprouting with feathers.

During the early years of Hollywood (1910s-1930s), “the finest movie costumers were, in fact, disciples of Poiret,” including Natacha Rambova, Gilbert Adrian, Orry-Kelly and our own, Travis Banton. 6

These names are generally considered part of the earliest wave of great Hollywood costume designers, working during the beginning of the golden years of film. Western fashion and costume design from the very beginning of both the couture, and film industry, has relied on appropriation of eastern culture to create novel design work. The first Hollywood version of Cleopatra was filmed in 1917, only about twenty years after the Lumière brothers screened the first ever film in a physical cinema. Egyptomania has been an vitally important element of Hollywood, essentially since its inception.

In 2023, renowned Egyptian archeologist Zahi Hawass, called for the British Museum to return the Rosetta Stone to Egypt. This Egyptian artifact is a 2,200 year old granodiorite stele, inscribed with hieroglyphics, ancient Greek and cursive Egyptian letters. It was acquired in 1802 by the British Museum from France, taken by Napoleon's colonial army from their time in Alexandria. As the former antiquities minister of the Egyptian government, Hawass has brought thousands of Egyptian artifacts back home. Hawass is one of the leading faces in the fight for the return of Egyptian objects, pilfered during colonial conquests.

To what extent does this sartorial obsession reflect the broader colonial nature of the western world? Hollywood’s representations of Cleopatra and other stories from Egyptian antiquity have been steeped in orientalism in the name of fashionable aesthetics as seen by the West. Both Cleopatra (1934) and Cleopatra (1963) commodify Egyptian motifs and symbols while imposing western beauty ideals onto stories of the Orient. Designers for over 100 years have cherry-picked elements of Egyptian art, to create collections or costumes which feel exotic and luxurious without ever engaging with any cultural or historical significance. This way of commodifying aesthetics is rooted in colonial practices of exploitation, where the value of these cultural items are redefined under western terms. This enduring fascination cannot be removed from the colonial frameworks which have historically driven appropriation, reinterpretation and the commodification of Egyptian, and more broadly, eastern visual culture. It is important to learn and understand how artists can engage with cultural symbols authentically. Acknowledging this trend within film and fashion history is essential in order to dismantle its ongoing effects, and to produce authentic stories, sartorially on-screen.

Style.com. “Alexander McQueen: Fall 2007 Ready-to-Wear.” YouTube, September 3, 2013.

Butchart, Amber. The fashion of Film: How cinema inspired fashion. London: Mitchell Beazley, 2016.

Butchart, Amber. The Fashion of Film: How Cinema Inspired Fashion. London: Mitchell Beazley, 2016.

"Cleopatra (1963)." Daily Telegraph [London, England], 26 Nov. 2014, p. 33. Gale General OneFile

“Cleopatra (1963 Film).” Wikipedia, December 6, 2024.

LaVine, W. Robert, and Allen Florio. In a Glamorous Fashion: The Fabulous Years of Hollywood Costume Design. London: Allen & Unwin, 1981.